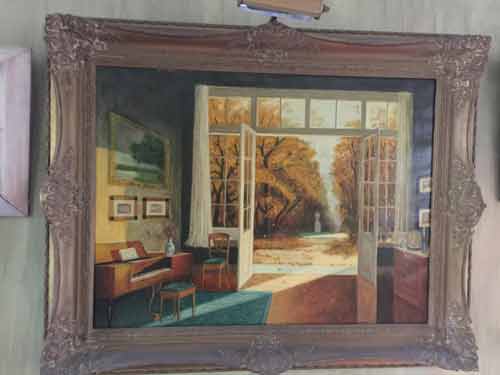

Several years ago, a local collector purchased at an online auction a mid-20th century painting of a sitting room with French doors that open onto an autumnal lawn with a stone statue in the middle of it. The painting was unsigned and inexpensive, but the collector was drawn to it because she could imagine herself living in the room.

Today she sort of does.

A few years after buying the painting, the collector attended a Lake Bluff History Museum Trinkets & Treasures sale, where a large garden statue caught her eye. The statue was a pastoral woman holding a bird’s nest; it was about four feet from head to toe and strapped in a prone position to a dolly. The statue was so chipped and broken that it couldn’t stand.

But like the painting mentioned above, the statue spoke to the collector. She and her husband surmised it was made of lead in Victorian-era England. Museum volunteers running Trinkets & Treasures knew only that a landscaper working at a local estate had been instructed to dispose of the statue but was hoping to find a buyer because he didn’t want it melted down for the value of the lead.

The collector and her husband offered half the asking price, explaining they didn’t know what it would cost to restore the sculpture. “There was no base, her feet were damaged, and there was no obvious way to get her standing again,” she said. Discussions were had, a deal was made, and soon the statue arrived at the collector’s house, still strapped to its dolly and looking forlorn.

The collector set out to uncover the mystery of what she and her husband were by then calling Lead Lady. Googling “Victorian lead garden sculpture”, she found an image of a similar sculpture at Kew Gardens in London. The Kew statue was called The Shepherdess and was made by sculptor John Cheere circa 1760-1770 – 100 years before the collector’s initial estimation. The collector learned Cheere’s sculptures were popular among the aristocracy of 18th Century England and beloved by the King of Portugal, who commissioned 98 Cheere sculptures to be shipped to the royal palace of Queluz in 1756.

That bit of information provided another clue: About 15 or so years ago all 98 of those statues were sent from Portugal back to London to be restored by a man named Rupert Harris. The collector emailed Harris photos of Lead Lady, and he confirmed the sculpture was a relatively important survival of a sculpture by Cheere, most likely dating from 1745 to 1760.

She learned that if properly restored, the sculpture could fetch between $12,000 and $40,000 (depending on who was in the auction house on the day it went up for sale).

The collector wanted to enjoy the sculpture, not sell it, but here in 21st Century America was anyone restoring 250-year-old, 350-pound lead sculptures? Having the sculptor’s name unearthed another key piece of information: Contact info for a man who had restored a similar Cheere statue for a client on the East Coast of the U.S.A.

There is more to the story – at first he declined the job, saying his wife didn’t want him working with lead anymore. A year passed with Lead Lady still strapped to her dolly in the collector’s garage until the artist called back to say he had changed his mind – or rather, his wife had – and he would do the job. The collector’s husband built a crate (no small feat for a 350-pound, 4-foot tall statue!), Lead Lady was shipped to the East Coast, iron rods in the legs were swapped for stainless steel, lead was welded, the patina researched and corrected, checks were written to the tune of a few thousand dollars …. and Lead Lady was restored to her original glory.

Lead Lady now stands firmly on a granite base and, as in the painting purchased years ago at an online auction, she can be seen from the collector’s sitting room through French doors that open onto an autumnal lawn with a stone statue in the middle of it.