The first time Jack Schuler inquired about buying lakefront property at Crab Tree Farm, he was kindly told no.

The second time he tried to purchase land there, his offer was quickly rejected.

And the third time? Third time’s the charm, as the ancient saying goes.

“I’m a lucky guy,” Schuler says.

He says it often.

Schuler’s courtship with Crab Tree Farm began some 50 years ago when he was a rising executive at Abbott Labs living with his wife Renate and their children on Lakeland Road, half a mile south of the farm. An avid sailor and windsurfer, his favorite place to ride Lake Michigan’s waves was out by “the bowl,” a unique section of lakefront where the transition from tableland to beach is gradual instead of steep. He found the wind on the water to be steadier there compared to along the bluff.

“One day in the early 1970s, I pulled my windsurfer up to Crab Tree Farm and spoke to the owner, William McCormick Blair, who was then in his late 80s,” Schuler remembers. “I asked if he would ever sell any lakefront property, and he said in a nice way that that would never happen.”

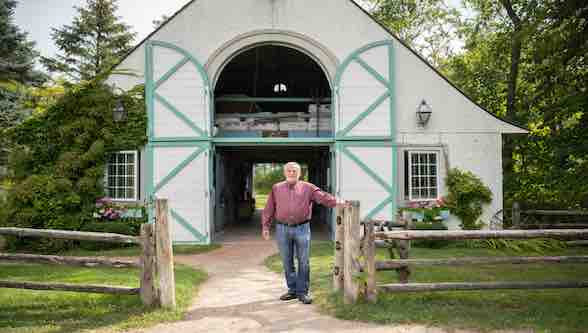

Schuler wasn’t the first to seek a piece of the 250-acre pastoral property that’s a few blocks north of Lake Bluff, 33 miles from Chicago and a world away from everywhere. The land includes the only working farm on Lake Michigan in Illinois, plus a savanna, forests, ravines, bluffs, a prairie, pine grove, duck pond, and more than half a mile of lakefront. One of the first things you see when you enter the grounds are sheep and horses grazing in a meadow.

Parcels of land at Crab Tree Farm have changed hands a few times since the 1830s when the area opened to settlement, but the section of the farm that has housed the barns and building complex visible from Sheridan Road has had only four owners in all this time. The first three were:

Federal District Judge Henry W. Blodgett, who purchased several lots amounting to 370 acres during the second half of the 19th century and created Ash Meadow Farm, where he bred cattle and hogs and operated a dairy. He died in February 1905.

Sugar broker Scott Durand, who in 1906 purchased 250 acres from the Blodgett estate for his wife, Grace. She moved her Crab Tree Dairy operation from the intersection of Sheridan Road and Crabtree Lane in Lake Forest. After a November 1910 fire destroyed the complex, Grace hired prominent architect Solon S. Beman to design state-of-the art barns and landscape architect Jens Jensen to design gardens.

Financier William McCormick Blair and his wife Helen Bowen Blair, who in 1926 bought 11 acres in the northeast corner from the Durands and built a lakefront summer home designed by David Adler. In 1950, the Blairs bought the farm buildings and 245 additional acres from the Durand estate and established a gentleman’s farm breeding hogs.

It was William McCormick Blair who in the early 1970s kindly told a wave-soaked Schuler that Crab Tree Farm’s lakefront would never be for sale. His three sons, William Jr., Edward and Bowen, had a different plan. In 1985, three years after the senior Blair died at age 97, the farm was on the market, divided into a dozen or so 15-acre lots.

That same year, 1985, John and Neville Bryan purchased 16 acres from the Blair estate, including the David Adler-designed lakefront home.

Also in 1985, Schuler was working on fulfilling his dream of owning a piece of the farm. Included in the Blair estate’s 1985 sale were two lake-front parcels at the bowl. Although Schuler had a sailor’s appreciation for the 250-foot-wide lakefront knoll, it could be problematic for a homeowner. This is because the gradual slope was created when a bluff collapsed in the 1950s during a period of high water.

The construction in 1911 of the Great Lakes Naval Station is considered a significant factor in the erosion problems along all of Lake Bluff’s lakefront. “It disrupted the naturally occurring lateral flow of sand,” explains Schuler of the Great Lakes harbor. “The south-flowing sand previously created sand bars that broke up the power of the waves before they hit the shore.”

William McCormick Blair saw the erosion happening and had 15 steel groins built in the lake to hold sand in place and help preserve the beach and bluffs at Crab Tree Farm. Two of the groins were farther apart than the other 13, and that’s where the bluff collapsed.

Nearly 60 years later, what would it take to prevent the rest of the bluff from failing? Lake Michigan was at a near record-high in 1985, threatening to undercut the groins. “This means that if the wave action gets to the clay part of the bluff, it immediately dissolves, and the water gets behind the groins and the bluff can erode up to 30 feet in one year. Basically sand, which does not dissolve, protects the bluff,” explains Schuler.

Also in the mid-1980s, experts were predicting the lake would rise another three feet. Schuler, who then was president and chief operating officer of Abbott, got an estimate for fortifying his 900 feet of shoreline from a marine engineering firm. The price, which involved two barges shipping tons of quarried stone from Wisconsin, was $900,000.

The Blair estate wanted $1 million for each parcel, but given the dire straits of the bluff, Schuler offered less than half the asking price for the two lots together, a total of 30 acres.

The Blair estate said no.

Schuler responded with a note of thanks for their consideration, and he enclosed the bid for barging in rock “in the event any future buyer wanted to know what the cost of protecting the bluff would be.”

A few days later, his offer was accepted.

“I’m a lucky guy,” Schuler says again.

His luck continued. Lake Michigan reached a high point in 1986, and ever since then the water level has fluctuated. At its lowest in 2013, the lake was almost six feet down from its mid-1980s high point.

In 1985 Schuler didn’t know that would happen, and either way the bluff needed fortification. He didn’t want to barge stone in via the lake if he didn’t have to. Seeking a lower-cost option, he found a contractor who could tackle the problem by land, using concrete from a demolished Lake County highway instead of quarried rock from Wisconsin. Trucks hauled 8’ x 10’x 2’ concrete chunks across the fields (there was no road to his property at that time) and used a Caterpillar with a large forklift to transport the material via the sloping bowl down to the beach. This was considered a win-win for everyone involved, because it gave the contractor a place to unload concrete at no cost.

The team fortified Schuler’s 900 feet of shoreline and John Bryan’s and Edward Blair’s, too, — a total of 1,800 feet combined. The bill was $70,000, which the neighbors divided equally by three. All these years later, the concrete is still in place, Schuler says.

(Fortifying bluffs with demolished highways was a common approach in the 1960s, ‘70s and ‘80s; several lakefront homeowners and the Lake Bluff Park District added massive amounts to the foot of their bluffs. Concrete from some of these projects has broken up over the years and migrated south during severe storms, landing on Lake Bluff’s public beaches. But that’s a story for another day …)

Back to Schuler and Crab Tree Farm. The Bryan-Schuler-Blair neighbors worked together on another plan in the 1980s that was even bigger than rescuing the bluffs. Explains Schuler: “John Bryan suggested that the three of us make an offer on all the non-lakefront lots.”

This was approximately 180 acres, essentially all the farm minus 15 acres that eventually went to Marian Pawlick Tyler. Bryan took ownership and control of the farm buildings, and the partners put most of the rest under a conservation easement, which is a voluntary legal agreement between a landowner and a land trust that permanently limits the use of the land to protect its conservation values.

When he bought his Crab Tree Farm lots, Schuler had never built a home before, and he felt an enormous responsibility given the storied location and that other buildings on the grounds were designed by award-winning architects. After a competitive vetting, Schuler chose architect Larry Booth, who among other accomplishments had designed Shoreacres’ clubhouse after fire destroyed the original 1924 Adler building in 1983.

For Schuler, Booth crafted a house from stone, stucco, slate and glass that works more like an accessory to the outdoors than a dominant feature of the landscape. “Larry felt that when sitting in the house, the eyes should always be drawn to the outside,” Schuler says. “The house should be subservient to the natural surroundings.”

There’s a lot to see out those windows – a pine grove in one direction, Lake Michigan in another, art sculptures on the patio, migrating birds in trees and feeders, horses in a pasture, and if you’re lucky, an eagle above.

You can also see the bowl, which Schuler himself filled with long-rooted native plants and grasses in the 1980s, and a native prairie that he converted from a cornfield several years ago.

Schuler was in his mid-40s when he bought his piece of Crab Tree Farm, and he says again and again it was luck that brought him there.

Luck, commitment, and reverence.

“I knew Crab Tree Farm was a very special place, and I didn’t want to screw it up,” he recalls. “What God had created in this beautiful natural paradise, could only be diminished by constructing buildings on it.”