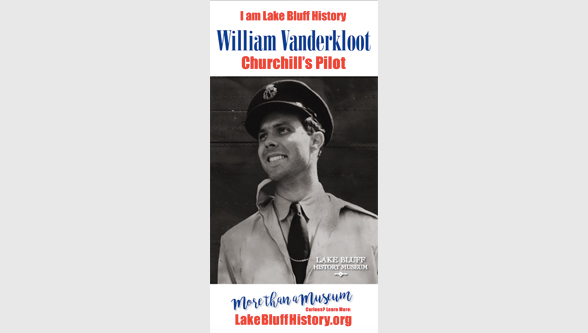

William Vanderkloot Jr. , “Billy”, was a Lake Bluff native, the son of William Vanderkloot, owner of a Chicago steel mill and Lake Bluff village president from 1917 to 1923, and Florence M Cary.

William Vanderkloot Jr. , “Billy”, was a Lake Bluff native, the son of William Vanderkloot, owner of a Chicago steel mill and Lake Bluff village president from 1917 to 1923, and Florence M Cary.

A quiet man with passionate interests, the blue yonder called him his entire life. In the early 1930s, he practiced flying by buzzing down Prospect Avenue in a wooden bi-plane—at treetop level. He became a commercial pilot before joining the Royal Air Force in World War II and serving as British Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s pilot.

As a teenager, Vanderkloot attended Culver Military Academy in Indiana. There he commanded the academy’s Black Horse Troop, a cavalry unit, at 16. But his greater interest was in flying: as a boy growing up in Lake Bluff he had long watched planes coming and going from the Glenview Naval Air Station and, during summers, he worked as a ground crewman for a local flying circus so he could be closer to the airplanes.

At his parents’ urging, he briefly studied law at the University of Virginia. But while he was there, he surreptitiously sold his car, bought a homemade aircraft with the money and, armed with a few self-funded flying lessons, promptly crashed it.

He later attended Parks Air College in East St. Louis, this time with his parents’ knowledge and financial support.

Vanderkloot was employed as a pilot for several years on the TWA route from New York to California, then went to Montreal in 1941–before the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor–and volunteered with the Royal Air Force to transfer long-range planes to Great Britain.

He was still doing that when he was ordered to RAF headquarters in July 1942 and asked by the RAF chief of staff if there was a safe and direct route from England to Cairo by air.

Vanderkloot responded he could make the trip in the specially modified B24 Liberator bomber Commando that he had just delivered to Prestwick, making just one stop in Gibraltar. He would first head eastwards over the sea and, after dusk, would turn sharply south, flying over Spanish and Vichy territory in Africa in the dark before turning east again for the Nile and approaching Cairo from the south. This route would avoid danger from land-based enemy aircraft in North Africa and Sicily without having to fly halfway around Africa.

The day after Vanderkloot made this suggestion, he found himself whisked to Churchill’s residence at No. 10 Downing Street. Churchill, clad in robe and slippers, offered the American pilot a drink, and a three-year relationship began that had Vanderkloot flying the British prime minister on sensitive diplomatic trips across war-torn Europe, North Africa and the Middle East.

As Churchill’s pilot, he conveyed the prime minister to Egypt to reshuffle command of the British army in North Africa, took him to high-level talks in Moscow with Joseph Stalin and to Turkey to determine that country’s wartime intentions.

Following the war, Vanderkloot headed the aviation department of Johns Manville Corp. in New York, where he was responsible for piloting executive jets and helicopters. He retired to Florida in 1970.

The Prairie-style home in which Vanderkloot grew up was built in 1911 on the corner of Prospect and Gurney Avenues. The family property extended south along the ravine where two additional homes have since been built.