Orphanage: the word conjures visions of dour, cold institutions with hungry children. A place where Christmas never happens.

The Lake Bluff Orphanage, known as the Lake Bluff Children’s Home since 1955, was different. Children there were well fed and clothed; attended public schools; participated in Scout troops and music lessons; and lived in “family units” with house parents dedicated to their care. The Home had a library, woodworking shop, print shop, preschool, and playgrounds.

And on Christmas?

“Christmas day was always very special. There were Christmas trees in every housing unit, and there were always gifts for us. Where they came from, we didn’t know,” says Wally Spitzer, who grew up in the Lake Bluff Children’s Home with his two brothers Gene and Greg in the 1950s and ‘60s.

From its inception in 1894 until it closed in 1969, the Children’s Home was a safe haven for thousands of children, providing adoption services, foster home placement, and year-round residential living through 8th grade. It started in a rented cottage for six children from Chicago, adding housing units as the resident population grew.

Eventually the Home totaled several buildings encompassing the entire north side of the 200 block of East Scranton Avenue, including five residential units (Judson Hall for girls, Wadsworth Hall for boys, and the Swift Hospital Building, which housed infants and very young children in one wing and medical and dental offices in another). The Home was supported by local benefactors whose names are still recognized around the community today: Harris, Swift, Lackie, Dick, Clow, Trowbridge, Moore – as in Raymond Moore, a former Children’s Home resident who was superintendent of Lake Forest High School from 1945-60.

As for Christmas in the Children’s Home?

Scrapbooks kept by house parents during that era show the children had a very busy schedule throughout the holidays, including dinners and parties, theater tickets, shopping outings, and visits to churches, hotels, and rotary clubs.

In the 1940s and earlier, most of the residents were orphans who would spend Christmas in the private homes of Lake Bluff and Lake Forest families. In the 1950s and ‘60s, the population had shifted to children whose families were unable to care for them on a regular basis. Some of the children went home for the holidays, while others remained in their dorms.

Wally remembers feeling the holiday magic.

“It was like any kid waking up with the anticipation of Christmas,” he says. “The house parents and staff were always trying to keep up the idea of Christmas – both the merry, jolly little man part, and being a Methodist home, it was also focussed on the religious part, the birth of Jesus. So you wake up, and like other kids you’d have a little bit of anxiety about ‘what did I get?’ And you’d go into the main area of the unit, where there was always a Christmas tree, and yes there were gifts there that were not there the night before.”

The Christmas that stands out the most in his memory was in the early 1960s, when he was 12 or 13 and his brothers were 11 and 9. All of the other children in the Lake Bluff Children’s Home went to their families for Christmas that year — except for the Spitzer boys.

You might think waking up alone in your dormitory on Christmas morning would be depressing. It wasn’t.

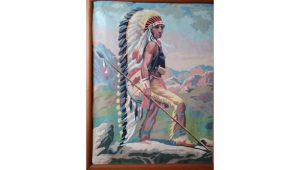

Wally remembers getting a paint-by-number kit of a Native American chief (which his house parents later framed and hung in the living room of his unit after he completed the painting). For dinner that night he sat at a table with his “relief house parent”, a 20-something man named John Beck who subbed for house parents on their days off. Wally recalls that John was a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War. “As far as I understand, he volunteered to do service work as opposed to serving in the military, and his service work was in the Lake Bluff Children’s Home.”

While Wally and John sat at one table in the Home’s big dining hall, Wally’s brothers sat at other tables with house parents from their dorms.

“John looked at me and said ‘This is ridiculous!’ So he went to the other two tables and told the house parents to take the time off, and John sat with me, Gene and Greg for dinner,” Wally says.

Having Christmas dinner with his brothers and the cool, young “relief house parent” was huge. And it got better. After dinner, John took the boys for a ride in his Chevrolet Corvair to see Christmas lights in Lake Bluff and nearby towns.

“We rode around and had a great time,” says Wally.

Wally lived in the Lake Bluff Children’s Home until he graduated 8th grade from Lake Bluff Junior High. After that, he lived for a year in a facility in Rockford, Illinois, until a new group home in North Chicago run by the Lake Bluff Children’s Home was completed. He has always remembered the Children’s Home and the positive effect it had on him, so much so that he has been a regular Lake Bluff History Museum volunteer dedicated to getting the Home’s records organized, digitized and into our online catalog.

And Wally himself was never forgotten.

As care shifted to foster homes instead of institutional settings in the 1960s, the Lake Bluff Children’s Home population steadily declined. The facility eventually closed, and in 1979 the buildings were demolished to make way for private homes.

Before the wrecking ball came, Wally’s former house parent reached out to him. The couple had kept the painting of the Native American chief that he had made all those years ago with the paint-by-number set he got for Christmas.

Would he like the painting back?

Wally said yes.